“When in Drought, Leave it Out”

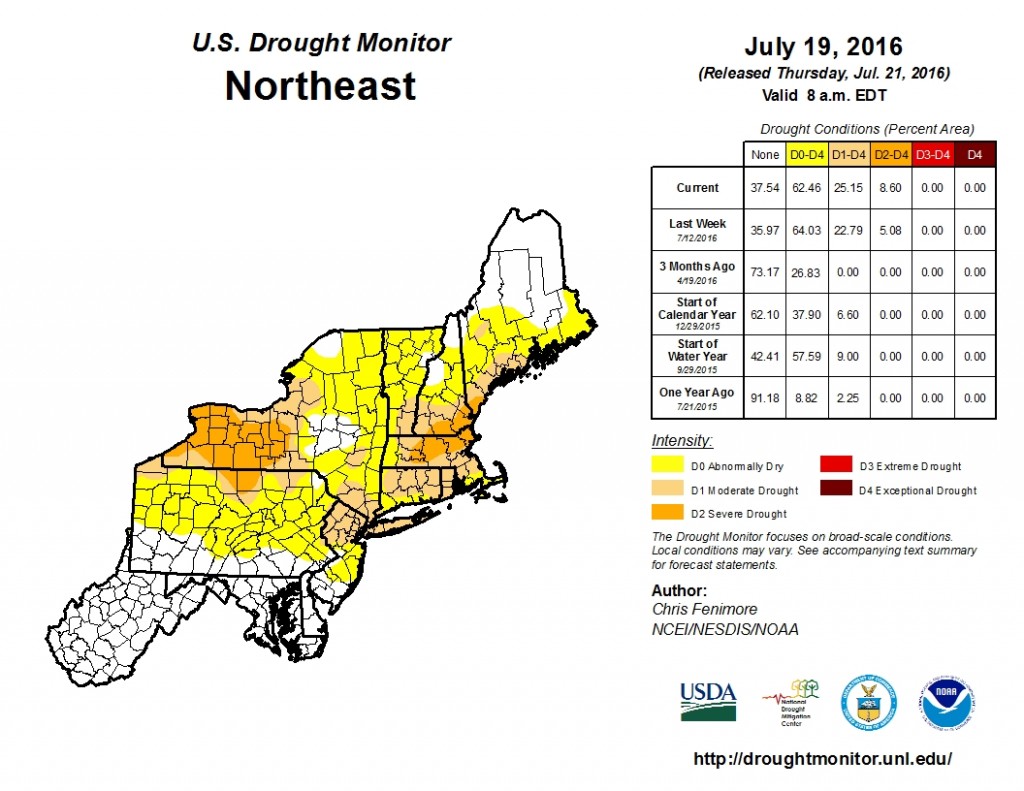

We don’t know who first coined that phrase, but like most meteorological rules of thumb, it tends to hold true most of the time. Currently in New England, especially Southern New England, a drought currently grips the region.

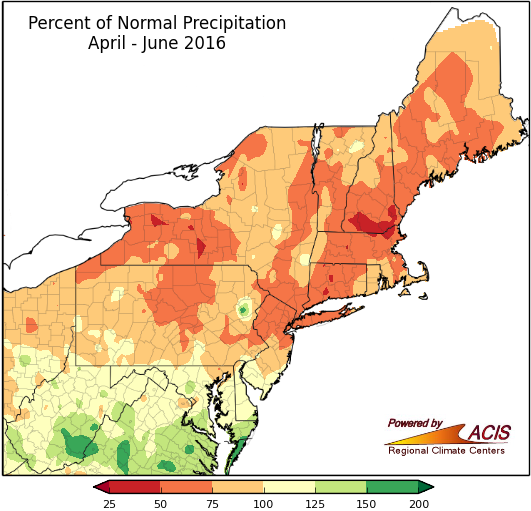

A persistent pattern has led to warm and dry conditions across the Northeast for the past several months. While scattered showers and thunderstorms have produced locally heavy rainfall in some areas recently, widespread rainfall has been lacking. Many cold fronts have come across the region with little rainfall and coastal storms are rare in the summer to begin with. Even waves of low pressure passing south of New England along stalled out cold fronts have been too far south to produce much rain across out area.

The dryness has been most noticeable since the beginning of June. Since June 1, Boston’s Logan Airport has recorded just 1.99″ of rain. This is the driest June/July on record in the city. The current record is 2.03″ from 1949. If Boston does not receive more than 0.04″ before Sunday night, a new record will be set (more on that later). In Worcester, the 3.18″ during the same timeframe is the 4th lowest total on record. In Lowell, 3.12″ of rain has been reported since June 1. This is the 8th lowest total on record.

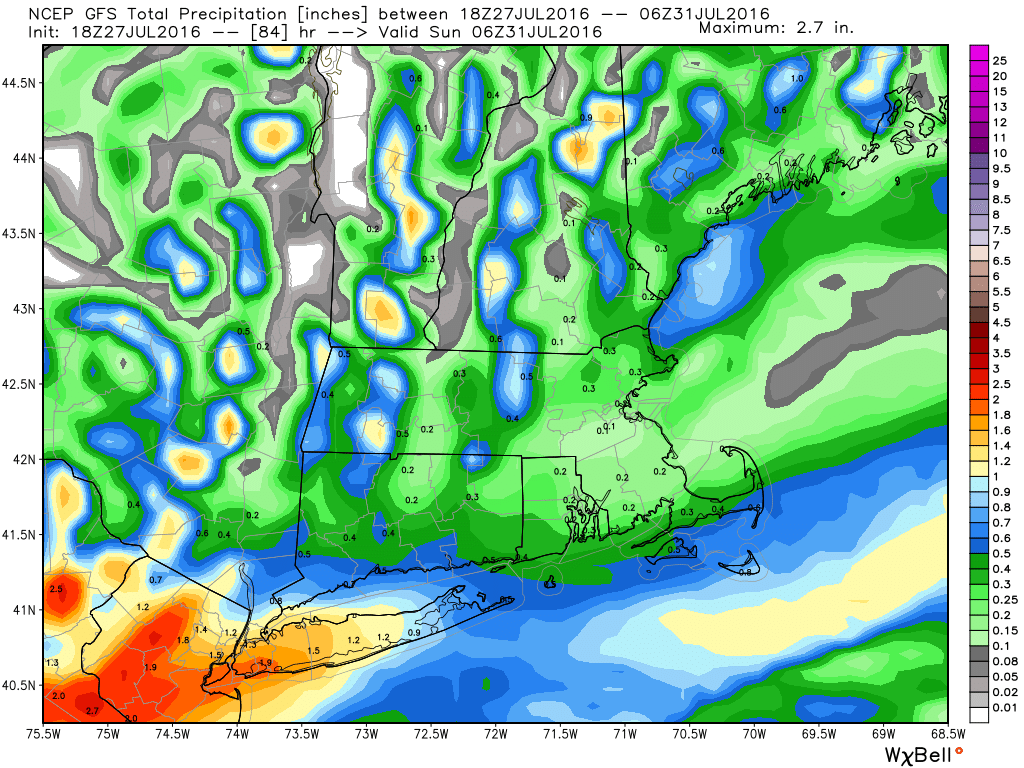

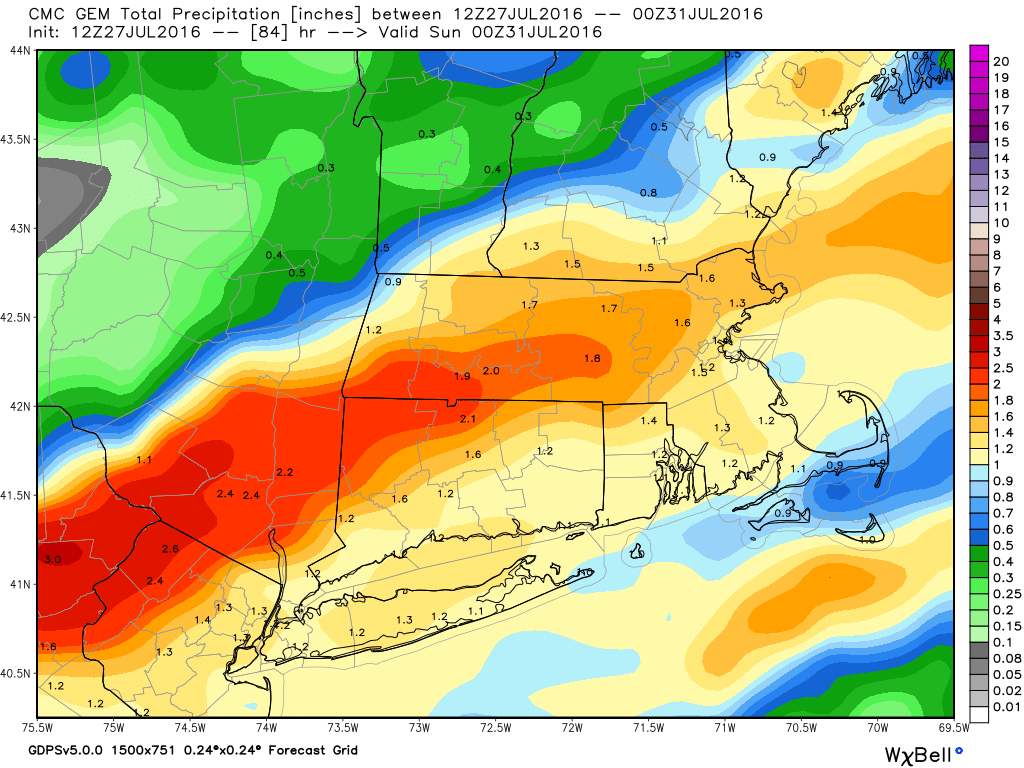

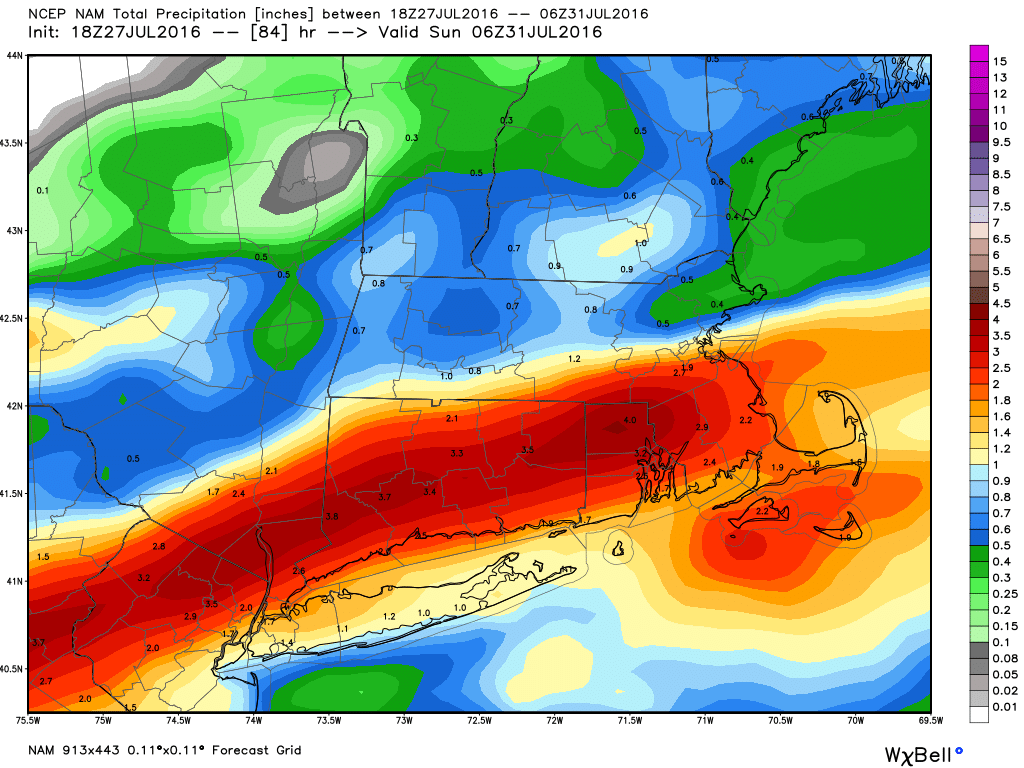

Is there any relief on the way? A cold front will move across the region late Thursday and early Friday, then stall out south of New England. A wave of low pressure will ride along the wave, passing south of us on Friday. This wave will produce locally heavy rain and thunderstorms across the Ohio and Tennessee Valleys on Thursday, before it heads for the Mid-Atlantic states Thursday night. The question then is, how far north does the low and its associated rain shield get. This is the same situation we often see in the winter when trying to determine if a storm will miss us completely, bury us with heavy snow, or come too close and give us rain instead of snow. Thankfully, we don’t have to worry about snow for another 3-4 months at least.

Right now, there are several different solutions among the models, which have a rather large impact on the forecast.

For the past few months, as we’ve mentioned previously, most of these storms have passed too far south to have much of an impact on us. For this reason, we’re inclined to lean that way with the forecast for Friday as well. Droughts feed on themselves, which is how the expression at the top of the page came into existence. When the ground is dry, there is even less moisture available for approaching systems. When there’s less moisture available, less rain falls. When less rain falls, the drought gets worse. So how do you break a drought? When you have one in the summer, usually, the answer is with a tropical system. Either a tropical storm/hurricane comes up the coast and slams into New England dumping copious amounts of rain on us, or one hits farther down the coast (North Carolina or the Gulf) and weakens inland and the remains of it move this way with heavy rainfall. The Summer of 1955 was hot and dry like this one has been. Then, in the span of a week in August, two Tropical Storms (Connie and Diane) brought record rainfall to the region, with widespread flooding. Of course, that’s not the preferred scenario. A more gradual transition to a wetter pattern is the best case scenario, but that isn’t how is usually works.

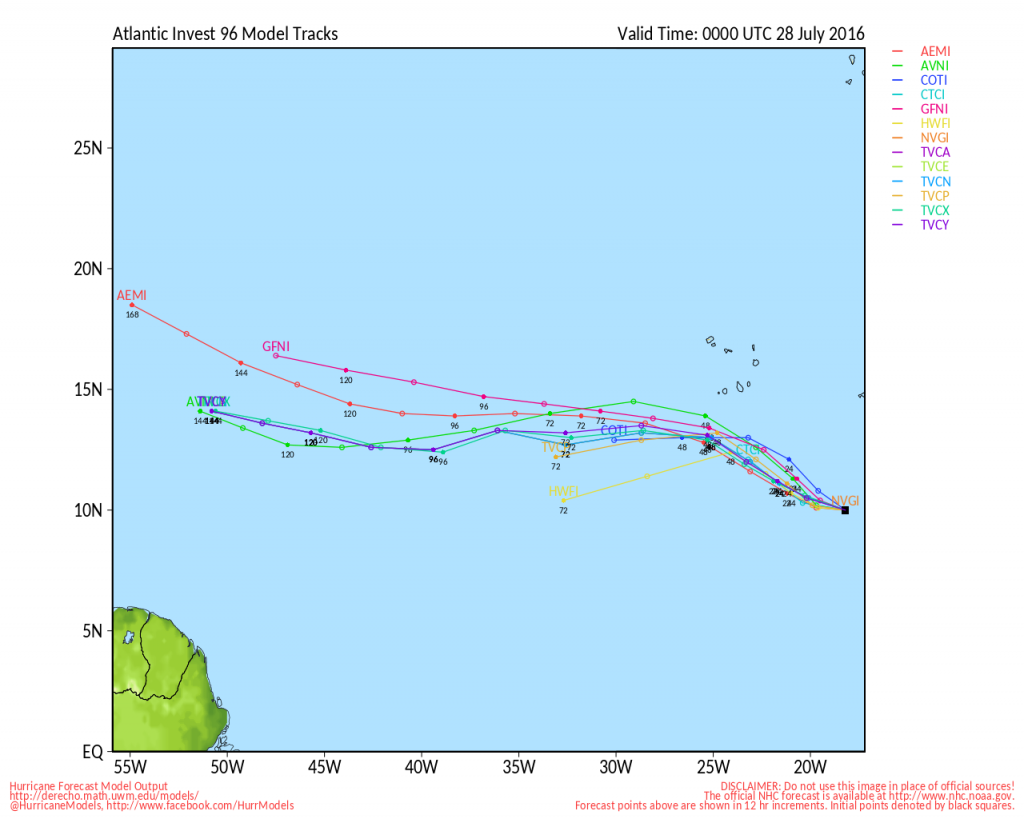

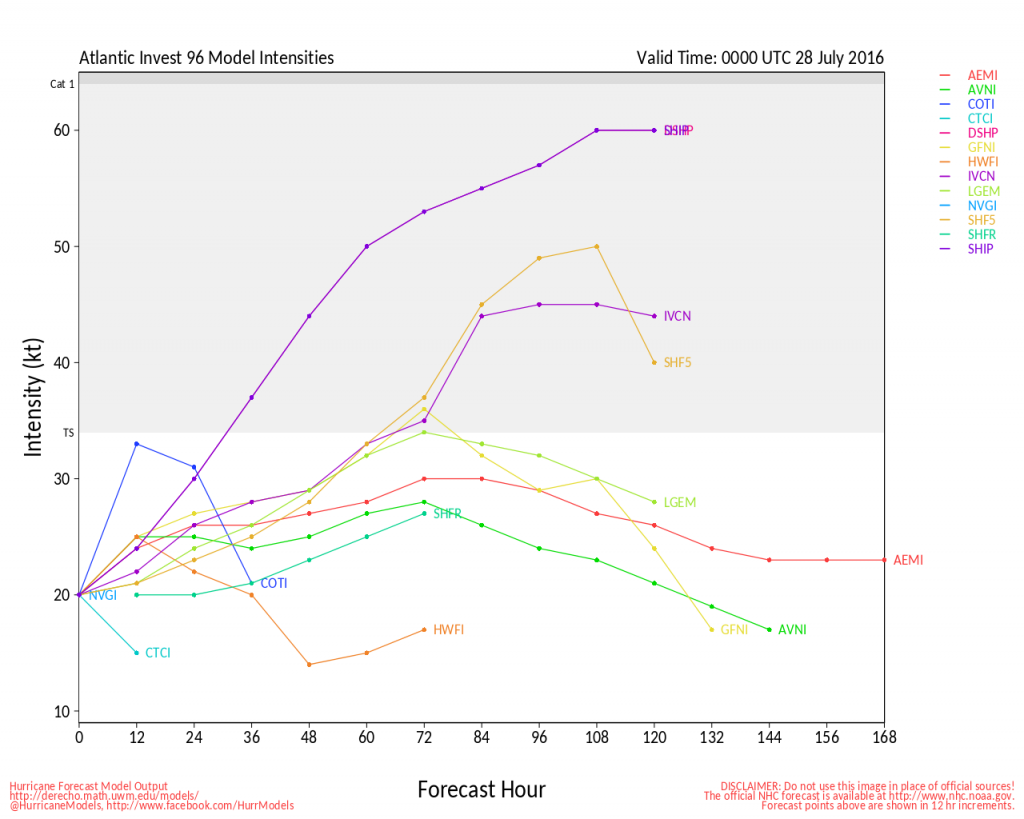

Speaking of the tropics, things may be starting to heat up. Since a record-setting June, there hasn’t been any activity at all in the Atlantic in July, but that could be changing. A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on Tuesday, producing plenty of shower and thunderstorm activity. Although some of that activity diminished today, conditions are still favorable for some development over the next few days. The odds of the system becoming a tropical depression are still fairly low, and the odds of it impacting any land, let alone New England are still fairly remote.

Now that we’re approaching the beginning of August, these waves should start to move off the coast of Africa every few days. At least a few of these will eventually become tropical systems as we approach the peak of hurricane season, which is late August into late September. Another area to watch is down near the Bahamas. Sometimes tropical systems form in this region, and they can quickly strengthen and head up the coast within a couple of days, which is exactly what Hurricane Bob did in August of 1991.