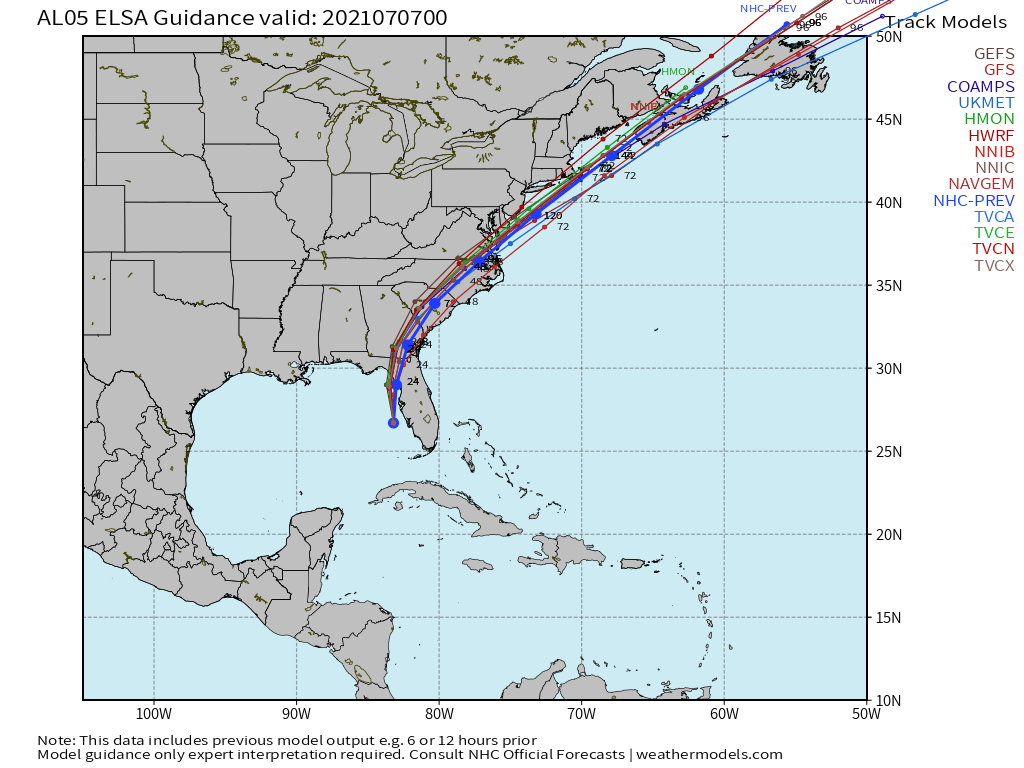

Tropical Storm Henri has made the long-awaited northerly turn and now is heading towards New England or Long Island.

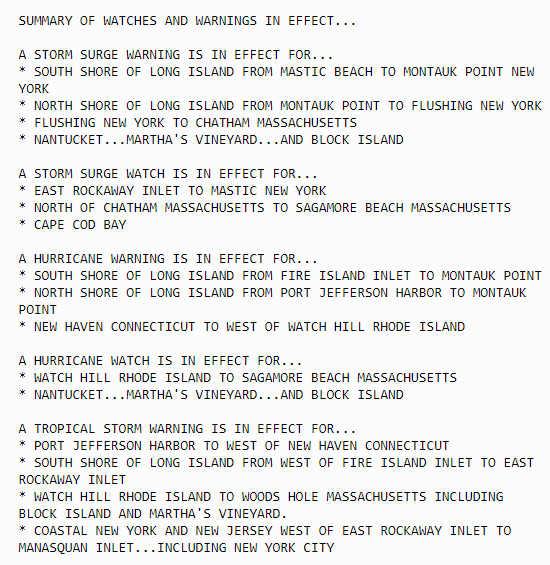

As of 11pm Friday, Tropical Storm Henri was centered about 615 miles south of Montauk, New York, moving toward the north at 9 mph. Maximum sustained winds were near 70 mph. Henri is expected to strengthen for the next 24 hours or so as wind shear begins to lessen and the storm remains over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream. Henri will likely become a hurricane on Saturday.

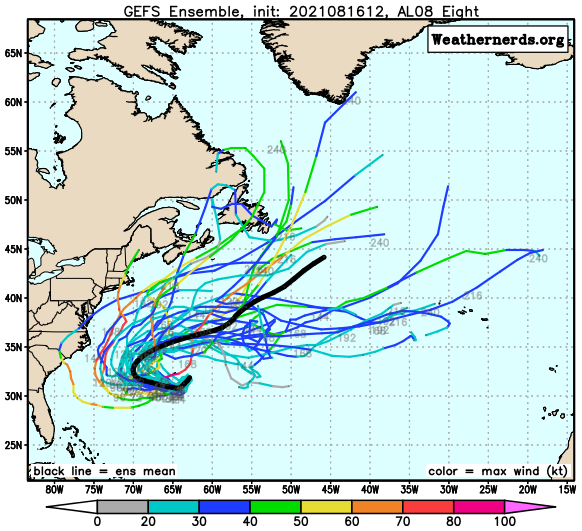

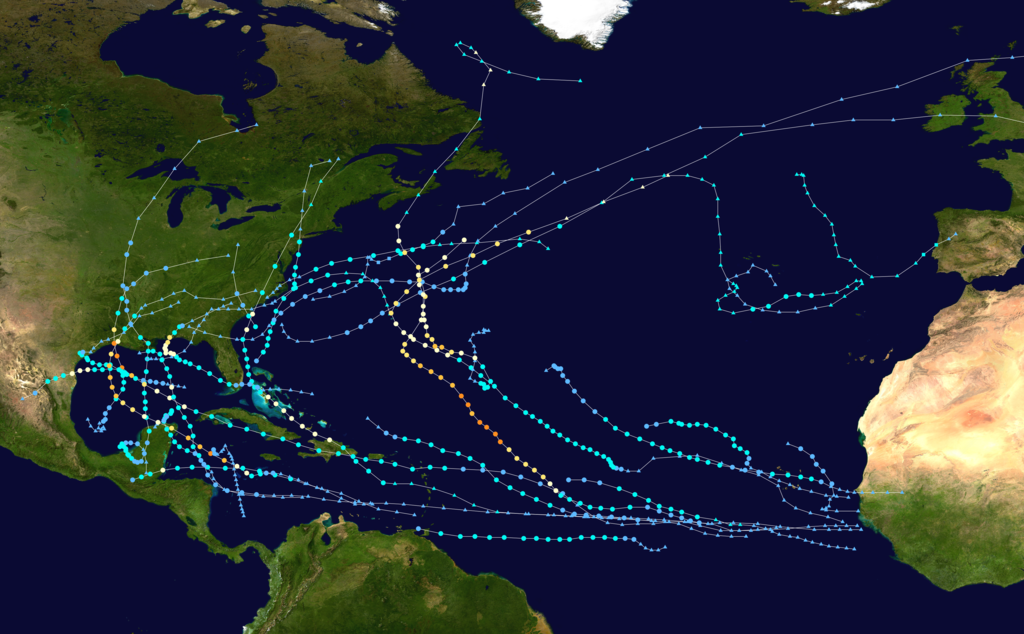

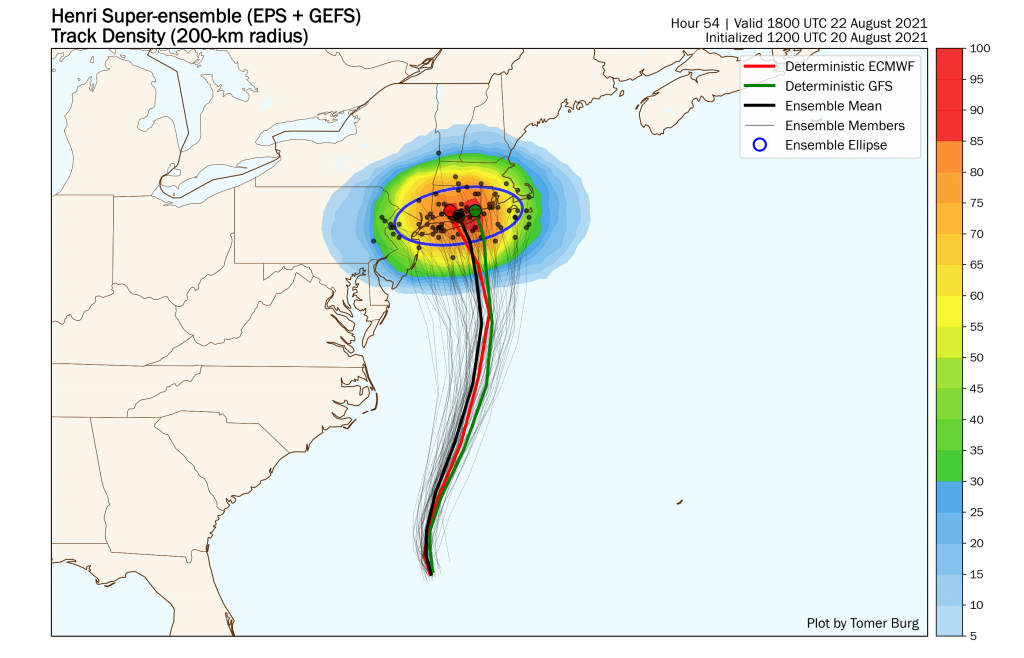

With a ridge of high pressure building in to the east of Henri, and an upper-level low pressure area developing over the Great Lakes, Henri will be steered northward for the next 24 hours, Beyond that, the upper-level low will start pull Henri northwestward and slow it down as it begins to approach Long Island or Southern New England. Since it will be over cooler water at that time, it will begin to weaken. Current forecasts show that Henri may still be a minimal hurricane at landfall, but there is also a good chance that it may weaken to a tropical storm by the time it reaches land.

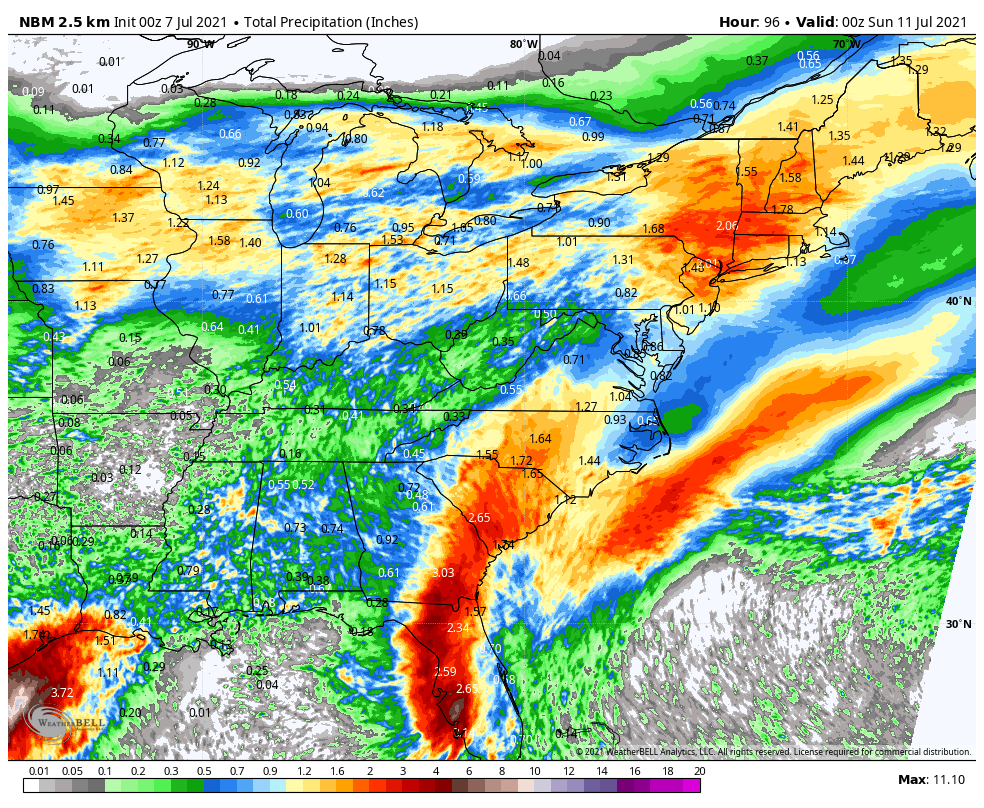

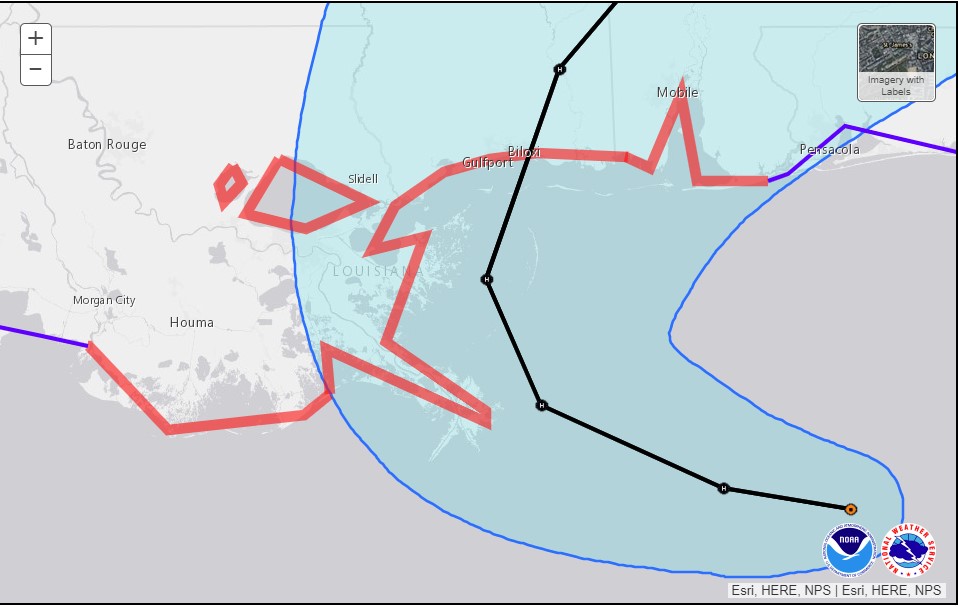

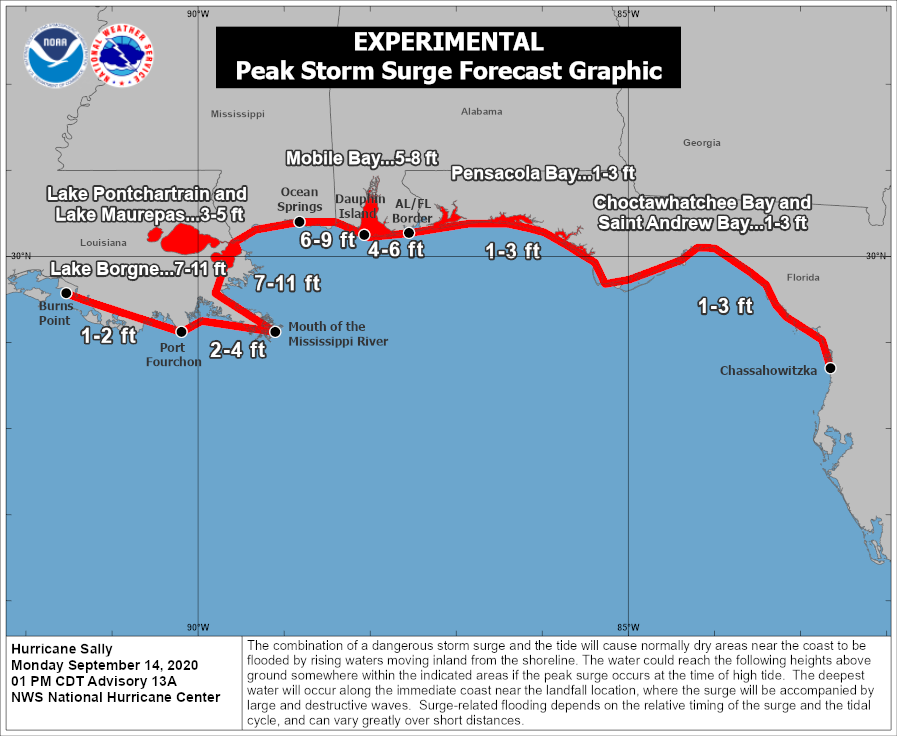

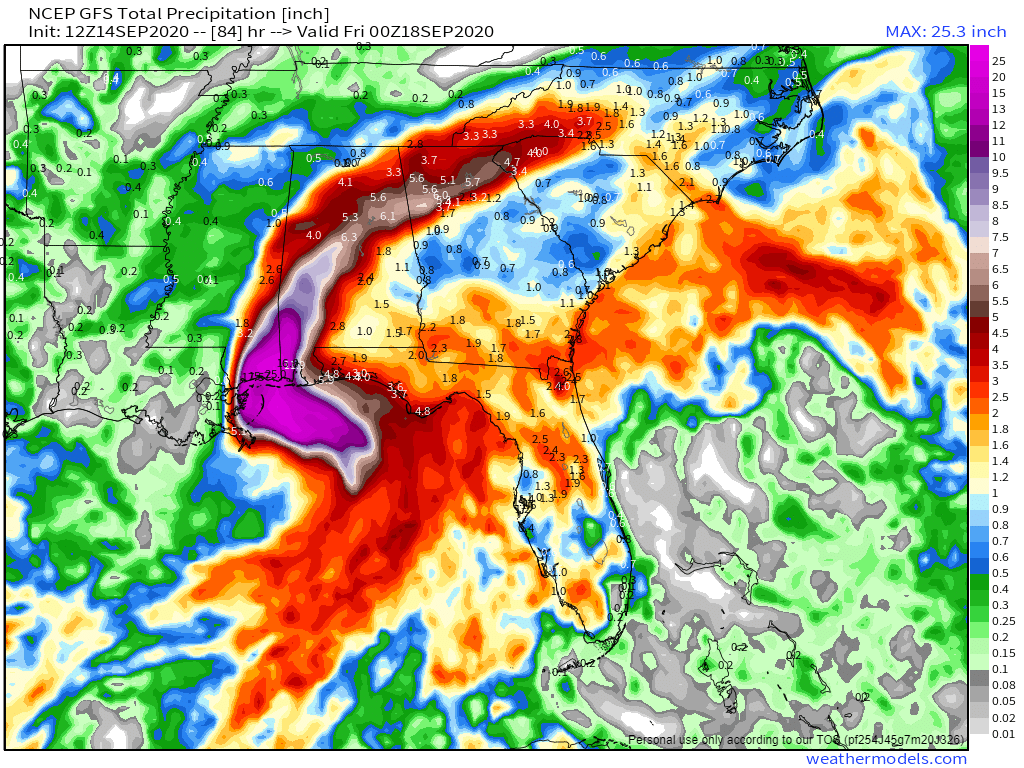

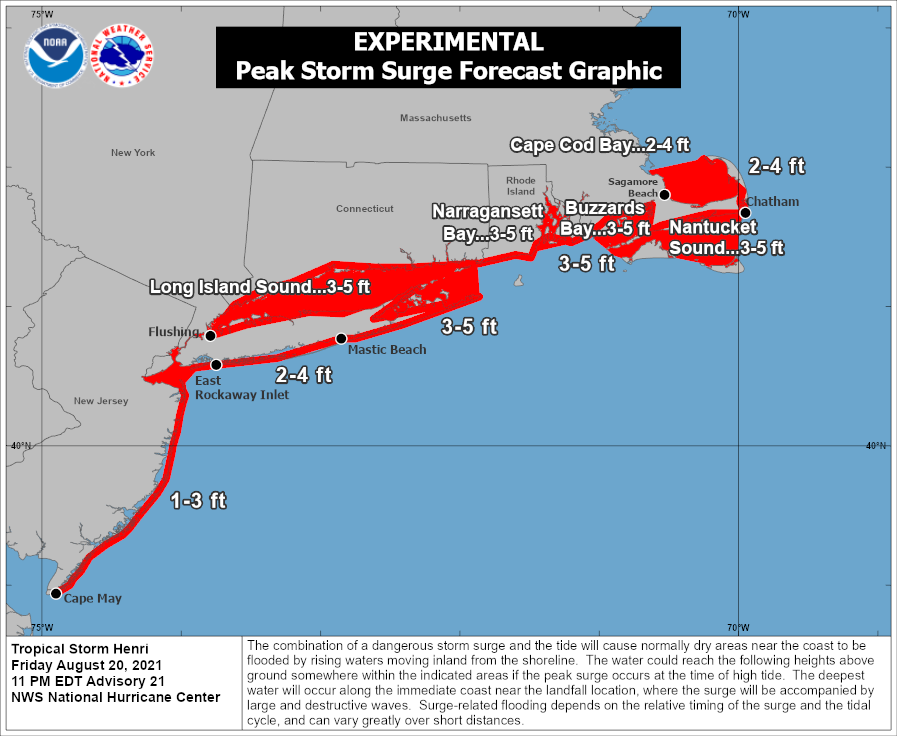

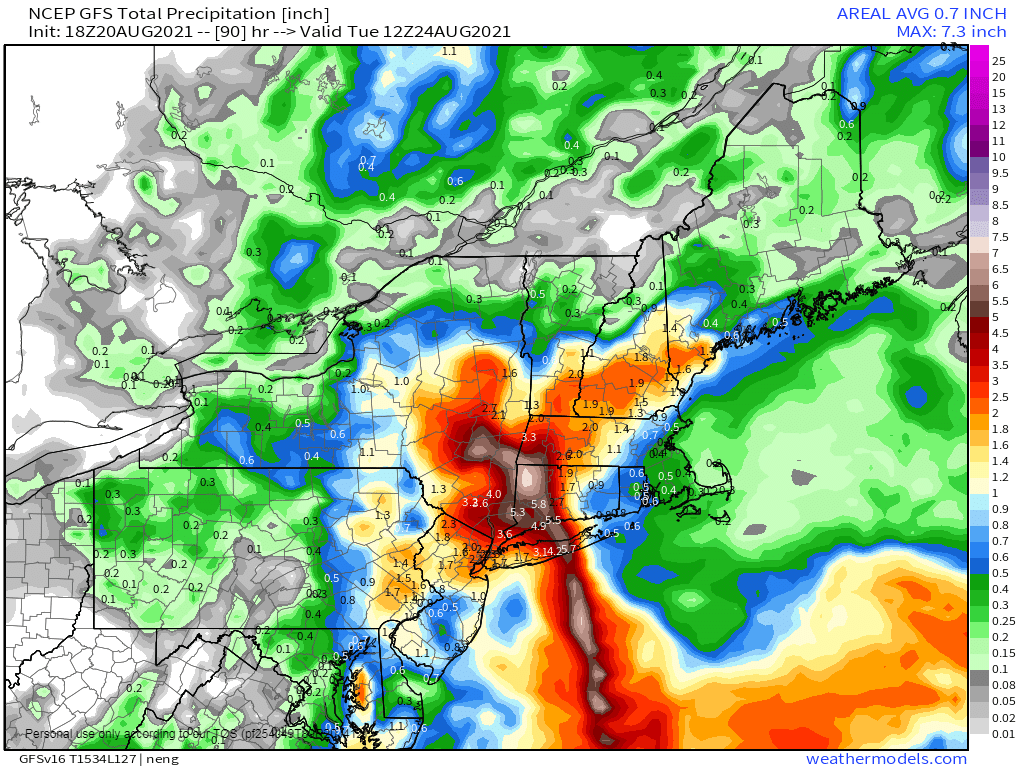

Although the exact track and intensity are still in question, the general impacts should be similar to most tropical systems that impact the Northeast. These systems tend to become lopsided, with the strongest winds mainly to the right of the center, and most of the rain shifting to the left of the track. The current forecast of a track towards eastern Long Island would mean that gusty winds and the highest storm surge would impact parts of Rhode Island and southeastern Massachusetts, including Cape Cod. The storm surge will be compounded by the fact that with a full moon on Sunday, tides will be astronomically high, exacerbating any storm surge flooding. The western track would also mean that the heaviest rain and greatest threat of freshwater flooding, would shift to Long Island, western portions of Connecticut and Massachusetts, and eastern New York.

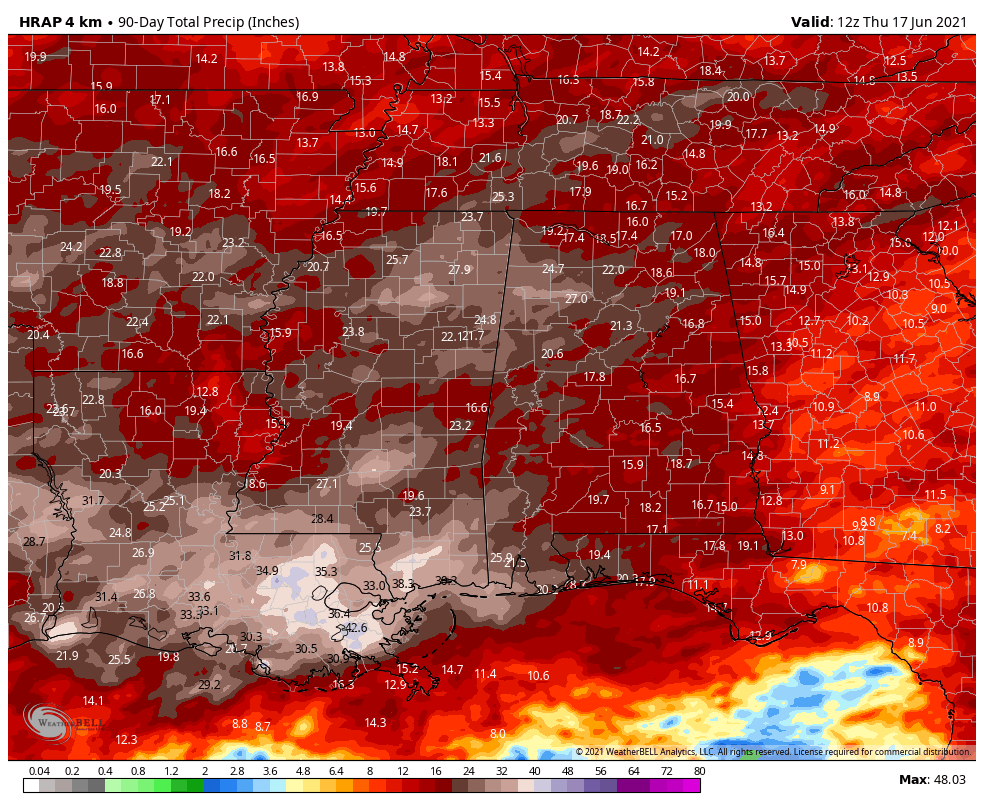

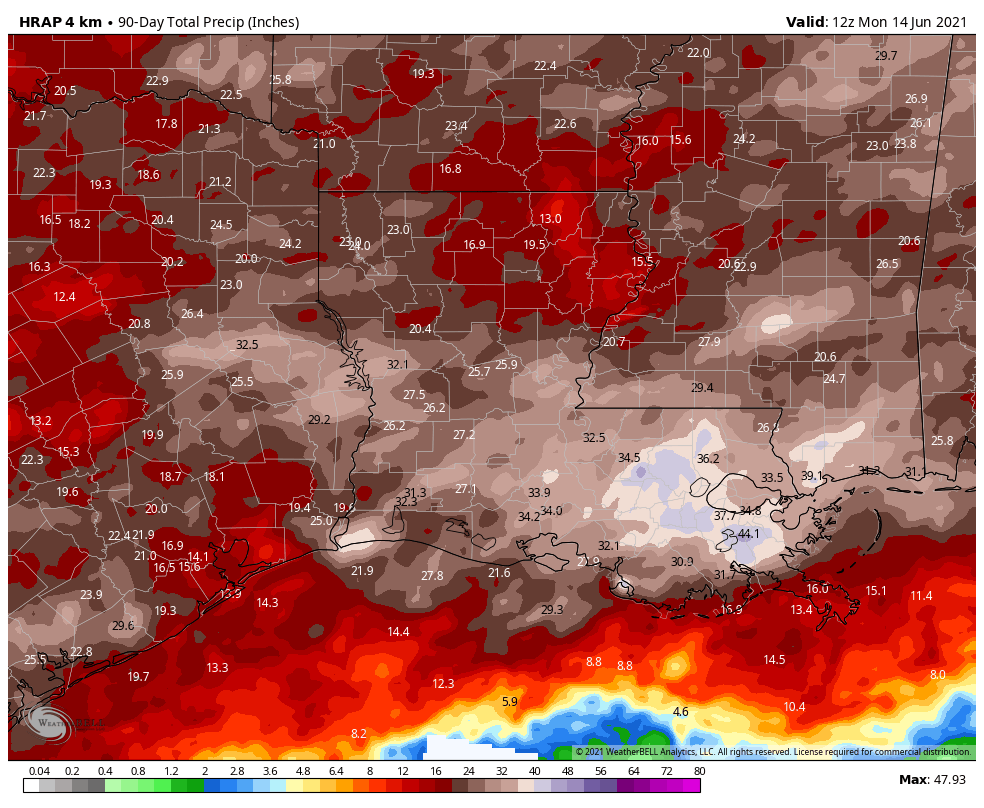

While the winds won’t be particularly strong across much of Southern New England, tree damage could be more extensive that you’d normally expect. It has been a very wet summer across the region, with many places receiving 10-20 inches since the beginning of July. As a result, the ground is saturated across much of the area, so it won’t take strong winds to knock trees over. It also will result in more extensive flooding in areas that receive heavy rain.

As the steering currents weaken late Sunday and Sunday night, Henri or what’s left of it, may stall out across western New England or eastern New York, then eventually start moving eastward, bringing more rain to parts of central and northern New England. Conditions will improve from west to east on Monday as the storm departs and high pressure starts to build into the region.